TOKYO -- Japan's nuclear safety agency raised the severity rating of the country's nuclear crisis Friday from Level 4 to Level 5 on a seven-level international scale, putting it on par with the Three Mile Island accident in Pennsylvania in 1979.

(SCROLL DOWN FOR LIVE UPDATES)

Ryohei Shiomi, a spokesman for the nuclear safety agency, said Friday that the agency raised the rating of the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear crisis on the International Nuclear Event Scale. The scale defines a Level 4 incident as having local consequences and a Level 5 incident as having wider consequences.

The hallmarks of a Level 5 emergency are severe damage to a reactor core, release of large quantities of radiation with a high probability of "significant" public exposure or several deaths from radiation.

A partial meltdown at Three Mile Island also was ranked a Level 5. The Chernobyl accident of 1986, which killed at least 31 people with radiation sickness, raised long-term cancer rates, and spewed radiation for hundreds of miles (kilometers), was ranked a Level 7.

France's Nuclear Safety Authority has been saying since Tuesday that the crisis in northeastern Japan should be ranked Level 6 on the scale.

The fuel rods at all six reactors at the stricken Fukushima Dai-ichi complex contain plutonium - better known as fuel for nuclear weapons. While plutonium is more toxic than uranium, other radioactive elements leaking out are likely to be of greater danger to the general public.

Only six percent of the fuel rods at the plant's Unit 3 were a mixture of plutonium-239 and uranium-235 when first put into operation. The fuel in other reactors is only uranium, but even there, plutonium is created during the fission process.

This means the fuel in all of the stricken reactors and spent fuel pools contain plutonium.

Other developments in the crisis overnight:

ATTEMPTS TO COOL REACTORS: Military fire trucks spray seawater for a second day on the stricken Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear complex in a desperate attempt to prevent its fuel from overheating and spewing dangerous radiation. A U.S. military fire truck joins six Japanese vehicles, but is apparently driven by Japanese workers. Japanese air force says some water appears to be reaching its target.

_ IAEA CALLS ACCIDENT "EXTREMELY SERIOUS." The head of the U.N.'s International Atomic Energy Agency says authorities are "racing against the clock" to cool the complex and calls the accident "extremely serious."

_ NEW POWER LINE NEARLY COMPLETE: The nuclear plant's operator, Tokyo Electric Power Co., hopes to finish laying a new power line to the plant on Friday to allow operators to restore cooling systems. But it is not clear if the cooling systems will still function.

_ MOMENT OF SILENCE: Tsunami survivors observe a minute of silence at the one-week mark since the quake, which struck at 2:46 p.m. Many are bundled up against the cold at shelters in the disaster zone, pressing their hands together in prayer. The twin disasters have left thousands dead and missing. Hundreds of thousands are staying in schools and other shelters, as supplies of fuel, medicine and other necessities run short.

_ IMPACT ON ECONOMY: The yen backs away from historic highs and Japanese shares rise after the Group of Seven major industrialized nations promises coordinated intervention in currency markets to support recovery from the disaster. The G-7 pledge comes a day after the yen soared to an all-time high against the dollar, possibly threatening Japanese exports. Japanese automakers, meanwhile, seek alternative parts suppliers to replace those knocked out by the earthquake, which forced most of the country's car production to a halt.

TOKYO -- Sirens wailed Friday along a devastated coastline to mark exactly one week since an earthquake and tsunami triggered a nuclear emergency, and the government acknowledged it was slow to respond to the disasters that the prime minister called a "great test for the Japanese people."

The admission came as Japan welcomed U.S. help in stabilizing its overheated, radiation-leaking nuclear complex and raised the accident level for the crisis, putting it on a par with the 1979 Three Mile Island accident in Pennsylvania. Nuclear experts have been saying for days that Japan was underplaying the severity of the problems at the Fukushima Dai-ichi power plant.

Still, Prime Minister Naoto Kan vowed that the disasters would not defeat his country.

"We will rebuild Japan from scratch," he said in a nationally televised address, comparing the work with the country's emergence as a global power from the wreckage of World War II.

"In our history, this small island nation has made miraculous economic growth thanks to the efforts of all Japanese citizens. That is how Japan was built," he said.

Last week's 9.0 quake and tsunami set off a cascade of problems by knocking out power to cooling systems at the nuclear plant on the northeast coast. Since then, four of Fukushima's six reactor units have seen fires, explosions or partial meltdowns.

The unfolding disaster has left more than 6,900 dead – exceeding the 1995 earthquake in Kobe, Japan, that killed more than 6,400. Most officials, however, put estimates of the dead from last week's disasters at more than 10,000.

It also has led to power shortages and factory closures, hurt global manufacturing and triggered a plunge in Japanese stock prices.

Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano admitted that Japan was not prepared for what happened.

"The unprecedented scale of the earthquake and tsunami that struck Japan, frankly speaking, were among many things that happened that had not been anticipated under our disaster management contingency plans," he said.

"In hindsight, we could have moved a little quicker in assessing the situation and coordinating all that information and provided it faster," he said.

The twin disasters have officially left more than 6,900 people dead and more 10,700 missing. Emergency crews are facing two challenges: cooling the nuclear fuel in reactors where energy is generated and cooling the adjacent pools where thousands of used nuclear fuel rods are stored in water.

Both need water to stop their uranium from heating up and emitting radiation, but with radiation levels inside the complex already limiting where workers can go and how long they can stay, it's been difficult to get enough water inside.

Water in at least one fuel pool – in the complex's Unit 3 – is believed to be dangerously low. Without enough water, the rods may heat further and spew radiation.

Military fire trucks sprayed the reactor units Friday for a second day, with tons of water arcing over the facility in desperate attempts to prevent the fuel from overheating and emitting dangerous levels of radiation.

Japan's nuclear safety agency ratcheted up its rating for the Fukushima crisis, reclassifying the nuclear accident from Level 4 to Level 5 on a seven-level international scale. The International Nuclear Event Scale defines a Level 4 incident as having local consequences and a Level 5 as having wider consequences. The 1986 Chernobyl disaster was rated as 7.

While nuclear experts have been saying for days that Japan was underplaying the crisis' severity, Hidehiko Nishiyama of the nuclear safety agency said the rating was raised when officials realized that at least 3 percent of the fuel in three of the complex's reactors had been severely damaged. That suggests those reactor cores have partially melted down and thrown radioactivity into the environment.

While Tokyo has welcomed international help for the natural disasters, the government initially balked at assistance with the nuclear crisis. That reluctance softened as the problems at Fukushima multiplied.

On Friday, though, Edano said Tokyo was asking Washington for help and that the two were discussing the specifics of the problem.

The U.S. said its technical experts are now exchanging information with officials from Tokyo Electric Power Co., which owns the plant, and with government agencies.

A U.S. military fire truck was also used to help spray water into Unit 3, according to air force Chief of Staff Shigeru Iwasaki, though the vehicle was apparently driven by Japanese workers. The Tokyo Fire Department said five of their trucks have joined in dousing operations at the unit.

The U.S. has also conducted overflights of the reactor site, strapping sophisticated pods onto aircraft to measure airborne radiation, U.S. officials said. Two tests conducted Thursday gave readings that U.S. Deputy Energy Secretary Daniel B. Poneman said reinforced the U.S. recommendation that people stay 50 miles (80 kilometers) away from the Fukushima plant.

Low levels of radiation have been detected well beyond Tokyo, which is 140 miles (220 kilometers) south of the plant, but hazardous levels have been limited to the plant itself. Still, the crisis has forced thousands to evacuate and drained Tokyo's normally vibrant streets of life, its residents either leaving town or staying in their homes.

The Japanese government has been slow in releasing information on the crisis. In a country where the nuclear industry has a long history of hiding safety problems, this has left many people, in Japan and among governments overseas, confused and anxious.

In the disaster zone, tsunami survivors, rescue workers and ordinary people observed a minute of silence Friday at 2:46 p.m. – the moment a week ago when the quake struck. Many were bundled up against the cold. As a siren blared, they lowered their heads and clasped their hands in prayer.

In the largely destroyed town of Hirota, 70-year-old Tetsuko Ito wept as she hugged an old friend she met at a refugee center. One of her sons was missing and another had been evacuated from his home near the Fukushima complex.

"Every day is terrifying. Is there going to be an explosion at the reactor? Is there going to be word my other son is dead?" she said.

She searched for her missing son for three days, then her car ran out of gas.

"I think he's dead. If he was alive, he would have contacted someone, somehow," she said. "My other son is alive, but we don't know if there's going to be a nuclear explosion."

If the situation gets worse in Fukushima, she said her son and his family will have to live at her already crowded house, which escaped the tsunami.

"It's strange when this destroyed area is a place someone would consider safe," she said.

Police said more than 452,000 people made homeless by the quake and tsunami were staying in schools and other shelters, as supplies of fuel, medicine and other necessities ran short. Both victims and aid workers appealed for more help as the chances of finding more survivors dwindled.

About 343,000 Japanese households still do not have electricity and about 1 million have no water.

At times, Japan and the U.S. – two very close allies – have offered starkly differing assessments over the dangers at Fukushima. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission Chairman Gregory Jazcko said Thursday that it could take days and "possibly weeks" to get the complex under control. He defended the U.S. decision to recommend a 50-mile (80-kilometer) evacuation zone for its citizens, wider than the 12-mile (20-kilometer) band Japan has ordered.

Crucial to the effort to regain control over the Fukushima plant is laying a new power line to the complex, allowing operators to restore cooling systems. Tokyo Electric missed a deadline late Thursday, said nuclear safety agency spokesman Minoru Ohgoda.

Power company official Teruaki Kobayashi warned that experts will have to check for anything volatile to avoid an explosion when the electricity is turned on.

"There may be sparks, so I can't deny the risk," he said.

Even once the power is reconnected, it is not clear if the cooling systems will still work.

The storage pools need a constant source of cooling water. Even when removed from reactors, uranium rods are still extremely hot and must be cooled for months, possibly longer, to prevent them from heating up again and emitting radioactivity.

By Jim Morris and Bill Sloat The Center For Public Intergrity

The nuclear crisis in Japan has prompted a re-examination of the safety net for nuclear power in the United States, with former regulators and safety advocates warning that gaps in the nation's regulatory armor could leave Americans similarly vulnerable to disaster.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the federal oversight body tasked with licensing and inspecting civilian nuclear facilities, too frequently relies on reports from the industry itself in monitoring for trouble, and is too lenient in meting out sanctions when it encounters violations, these critics say.

Though the commission posts inspectors at every plant, several independent and government reports note that these on-site observers document only a fraction of the events they observe on a daily basis.

"This co-dependent relationship between the industry and the NRC is stronger than the SEC and their relationship with Wall Street," said Robert Alvarez, a former advisor in the Department of Energy, and now a senior scholar on nuclear policy at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington. The SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) is oft-blamed for failing to adequately police the financial system in the years before the recent banking crisis.

A report released Thursday by the Union of Concerned Scientists, an environmental safety group, documents a series of inconsistent approaches used by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission when encountering major problems at plants over the last year, making enforcement appear haphazard.

In one case, at the Indian Point Nuclear Power Plant in New York, NRC inspectors allowed a leaking water containment system to persist for more than 15 years despite documentation of the problem, according to the report. A spokesman for Entergy, the utility that runs Indian Point, said the leaking is not "ideal," but that the water stays on site and does not pose a risk to the environment.

At the Calvert Cliffs plant in Maryland, a leaking roof that workers had known about for eight years caused an electrical short in 2010, forcing a shutdown of two reactors.

A spokeswoman for the NRC said that officials at the oversight agency were aware of the report, but had not been able to review it in depth because of attention to the events in Japan.

"The NRC remains confident that our Reactor Oversight Program, which includes both on-site and region-based inspectors, is effectively monitoring the safety of U.S. nuclear power plants," the spokeswoman wrote in an e-mailed statement.

The report from the Union of Concerned Scientists asserts that the NRC is only able to audit about 5 percent of activities at nuclear plants across the country in any given year, and that regulators are often too focused on the minutiae of individual violations instead of addressing systemic problems at a plant that may have led to deficiencies.

"The NRC must draw larger implications from narrow findings for the simple reason that it audits only about 5 percent of activities at every nuclear plant each year," wrote David Lochbaum, a nuclear engineer who authored the report for the Union of Concerned Scientists. "Each NRC finding therefore has two important components: identifying a broken device or impaired procedure, and revealing deficient testing and inspection regimes that prevented workers from fixing a problem before the NRC found it."

The report looked at 14 "near-misses" over the past year - events that required a special investigations team from the NRC to do a detailed inspection after a problem occurred. Many of the issues involved electrical shorts or deficient equipment at various plants that led to fires or unplanned shutdowns of the reactors.

One of the more egregious examples cited involved the HB Robinson plant in South Carolina, operated by Progress Energy, which had to shut down reactors twice in six months due to mechanical failures and electrical shorts. In the first case, an electrical cable that was not up to standards and had been installed in 1986 caused the power shortage leading to the shutdown.

Nonetheless, the majority of the violations were classified as "green" - the lowest level of sanction - which typically do not result in any monetary fine and require only formal written responses.

At the Brunswick Nuclear Power Plant in North Carolina, also operated by Progress Energy, the NRC's report from the time documented confusion and delays in responses among the plant workers after a gas was inadvertently released at the plant. The release should have led workers to activate nearby emergency response shelters and issue warnings to local, state and federal government officials, but the personnel did not know how to activate such alarms.

Eventually plant managers had to step in, and the alarms were only triggered after the federally mandated deadline. Despite the major failure in emergency response, the company was cited with only one potential monetary violation.

A spokesman for Progress Energy said the company has since installed more modern notification systems and increased the number of drills to twice-a-year, up from once every two years.

"We have taken specific actions to address each of the events last year that led to special inspections," the spokesman said in a written statement.

At the Honeywell Specialty Materials plant in Metropolis, Ill., the sole U.S. refinery that processes uranium for use in nuclear power plants, a union lockout has left temporary workers in charge of the facility. The locked-out members of United Steelworkers have erected 42 crosses in front of the Honeywell plant in memory of coworkers who succumbed to cancer in the past decade. Twenty-seven smaller crosses represent colleagues who survived a brush with cancer.

When the plant began hiring replacement employees after the June lockout, the NRC found that management coached candidates on how to properly answer questions on a required examination to work there. According to the NRC, the temporary workers were given answers prior to questioning and were helped during the course of the evaluation process if they became confused.

"The labor force was locked out and the Honeywell facility was trying to qualify as many operators as they could to make sure the plant could operate," NRC inspector Joe Calle said. "The process got overwhelmed, so to speak."

The NRC slapped Honeywell with a violation, and stopped the hiring process. Last fall, the NRC noted in a report that all the temporary workers had been retrained at the plant. The commission expressed assurances that the plant is being safely run.

But the commission has also cited the Metropolis Honeywell plant for a series of other violations since the lockout began, including an uncontrolled furnace ignition resulting when "operating procedures were not followed," according to a letter from the NRC to Rep. Jerry Costello (D-Ill.)

The NRC says it has no definitive proof that temporary workers were at fault, and that the violations were similar to earlier problems that were present when Union workers were working on site. But the locked-out union members pin the troubles on an inexperienced work force that was never fully vetted by the required examinations.

"A lot of people could open up a manual and go by that manual, but in an actual emergency it takes knowledge and experience to be able to handle it correctly and quickly," said a spokesman for the Steelworkers Local 7-669, John Paul Smith.

Data from the U.S. Geological Survey and other sources suggest, for example, that “the rate of earthquake occurrence … is greater than previously recognized” in eastern Tennessee and areas including Charleston, S.C., and New Madrid, Mo., according to the NRC document. There are 11 reactors in Tennessee, South Carolina and Missouri.

GI-199, a collaborative effort between the NRC and the nuclear industry, has taken on new urgency in light of the crisis in Japan. “Updated estimates of seismic hazard values at some of the sites could potentially exceed the design basis” for the plants, the NRC document says.

NRC spokesman Roger Hannah said the exercise was never meant to provide “a definitive estimate of plant-specific seismic risk.” Rather, he said, it was done to see if certain plants “warranted some sort of further scrutiny. It indicates which plants we may want to look at more carefully in terms of actual core damage risk.”

The information collected under GI-199 has been shared with operators of all 104 reactors at 64 sites in the U.S., Hannah said, and NRC officials are in the process of determining whether any plants require retrofits to enhance safety. He added that the assessment indicated “no need for any immediate action. The currently operating plants are all safe from a seismic standpoint.”

Every proposed nuclear plant in the U.S. already must undergo an extensive environmental review that examines the site’s seismology, hydrology and geology, NRC spokesman Joey Ledford said.

The Nuclear Energy Institute, a trade group, said in a statement this week that nuclear plants “are designed to withstand an earthquake equal to the most significant historical event or the maximum projected seismic event and associated tsunami without any breach of safety systems.” The U.S. Geological Survey updates its seismic hazard analyses roughly every six years, the institute said, and “the industry is working with the NRC to develop a methodology for addressing” newly recognized hazards.

Asked why GI-199 has taken nearly six years, Ledford said, “These are very complicated issues. We’re talking about 64 plant sites. It’s not a small task.” According to a January 2010 NRC document, GI-199 was to have been completed last April. An agency document dated January 2011 says the completion date is “to be determined.” The NRC blamed the delay on issues relating to the release of a copyrighted Electric Power Research Institute report to an NRC contractor and on “the desire for internal and external stakeholder agreement.” Over the years, the NRC often has been criticized for taking too long to resolve important safety issues. One example: what’s known in the industry as a loss-of-cooling accident, regarded as the most serious event that can happen at a reactor. Since the 1980s, the NRC has been looking into the problem of clogged emergency core cooling pumps in boiling water reactors. The issue has not been resolved. The Fukushima Daiishi reactor and 35 reactors in the U.S. are boiling water reactors.

Japanese regulators, too, recognized that they had understated seismic risks to their nuclear generating facilities, and were pushing utilities to engineer plants better able to resist tsunamis.

At a previously scheduled NRC conference in suburban Washington last week, just days before the 9.0 earthquake that crippled Fukushima Daiichi, Japanese officials briefed their American counterparts on four quakes in Japan since 2005 that exceeded design standards for some nuclear plants. In no case was the damage severe. Nonetheless, the Japanese were re-evaluating seismic data and moving to buffer the plants.

At the conference, the Japanese delegation said that tsunamis were a particular concern for coastal plants located in seismic zones. The officials said the industry should build upon “significant progress in tsunami hazard assessment, tsunami warning and mitigation and tsunami resistant design.”

EVENTS GET AHEAD OF THE REGULATORS Earthquakes can occur in all sorts of locales. In January 1986, a late-morning quake measuring 4.96 on the Richter scale was blamed for cracks in the Perry Nuclear Power Plant on Lake Erie near Cleveland. At first, people thought it wasn’t a quake; speculation focused on an explosion somehow related to the Challenger space shuttle disaster or an attack on New York City. The newly licensed plant’s reactor was to be fueled for the first time the next day. Officials and the public were caught by surprise; few suspected Northeastern Ohio was in an active seismic zone. But it is. Experts determined that the quake’s epicenter was 11 miles from the plant, which has been dogged by controversy ever since.

A previously unknown fault line also runs near the Indian Point plant, 24 miles north of New York City. Indian Point’s two units are up for relicensing by the NRC in 2013 and 2015, respectively, and a fierce battle is expected. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, while campaigning last year, called for Indian Point to be closed. Now he has ordered a safety review of the plant. In a 2008 paper, four researchers from Columbia University reported that “Indian Point is situated at the intersection of the two most striking linear features marking the seismicity and also in the midst of a large population that is at risk in case of an accident at the plants.” Indian Point’s two reactors, the researchers noted, “are located closer to more people at any given distance than any other similar facilities in the United States.”

The plant’s operator, Entergy Corp., issued a statement saying all its nuclear plants “were designed and built to withstand the effects of natural disasters, including earthquakes and catastrophic flooding. The NRC requires that safety-significant structures, systems and components be designed to take into account the most severe natural phenomena historically reported for each site and surrounding area.”

Even where nuclear plants have been built in established zones of potentially severe earthquakes, such as California, scientists are often far ahead of the regulators in raising questions about the safety of the plants. The California Coastal Commission, for example, has been sparring with the NRC over what the commission claims are under-appreciated seismic risks at the San Onofre plant, on the Pacific Ocean south of Los Angeles. After a review several years ago, the commission said “there is credible reason to believe that the design basis earthquake approved by [the NRC] at the time of the licensing of [San Onofre Units] 2 and 3 … may underestimate the seismic risk at the site.” Mark Johnsson, a geologist with the commission, said GI-199 suggests that the NRC is taking such risks more seriously.

“In California, we’ve had our differences with the NRC,” Johnsson said, “but they are saying there is credible evidence the earthquake risk in large portions of the country may have been underestimated for decades. We have objected to things they have done. We have not particularly relied on their work here in California. But in this instance they are trying to get it right, I think. They are looking at the new science and are open to it. Right now, there is insufficient data to understand how these faults work at great depths under these power plants.”

The Coastal Commission has accused the NRC of trying to weaken safety regulations for spent fuel storage sites in areas prone to tsunamis and quakes. It said the most likely incident on the West Coast would involve a major earthquake “immediately followed by inundation of the damaged facility by a tsunami.” That is exactly what happened in Japan.

In a 2002 letter to the NRC, the commission’s executive director, Peter Douglas, said the storage areas should have safety standards “consistent with the requirement for nuclear power plants.” He said the NRC hadn’t offered any logical explanation for trying to weaken the rules.

Douglas wrote, “It is especially important that an appropriate standards for … tsunamis be applied because perhaps the most likely scenario for release of radiation to the environment is damage to an [independent spent fuel storage installation] or [monitored retrievable storage installation] during a major earthquake, immediately followed by inundation of the damaged facility by a tsunami.”

The NRC rejected Douglas’s complaint and lowered the seismic standards for spent fuel storage.

Joe Litehiser, a Bechtel Corp. researcher, has studied the implications of earthquakes on licensing of proposed new nuclear plants in the central and eastern U.S. Litehiser said there is more seismological information available now than there was decades ago, when the existing plants were built. Scientists now believe, for example, that major earthquakes occur around Charleston, S.C., every 550 years instead of several thousand years apart, as industry models had assumed.

This is relevant not only because South Carolina has seven active reactors, but because four more units are planned for the state. Applications filed by the proposed operators, Duke Energy and South Carolina Electric & Gas, seek NRC permission to build Westinghouse Advanced Passive 1000 (AP1000) reactors in Fairfield and Cherokee counties. In a March 7 letter to NRC Chairman Gregory Jaczko, U.S. Rep. Edward Markey, D-Mass., wrote that one of the agency’s own experts believes the AP1000’s shield building could “shatter like a glass cup” in the event of an earthquake or a similar disaster.

Aaron Mehta and Susan Stranahan contributed to this story.

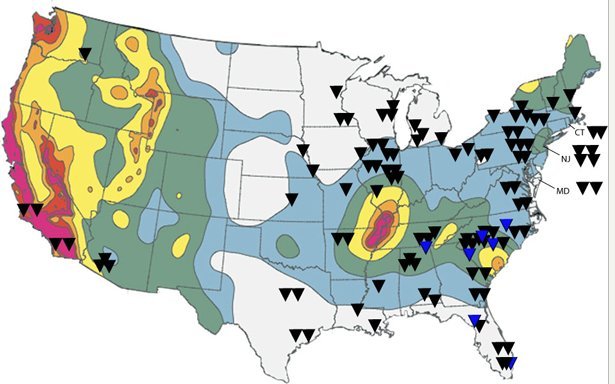

What are the risks of an earthquake beneath a reactor near you? This image combines a 2006 map by the United States Geological Survey showing varying seismic hazards across the U.S. with locations of nuclear reactors. Reactors in black are active; reactors in blue are proposed sites for the new model known as the AP1000. Probability of strong shaking increases from very low (white), to moderate (blue, green, and yellow), to high (orange, pink, and red). Credit: Kimberly Leonard/Center for Public Integrity.

What are the risks of an earthquake beneath a reactor near you? This image combines a 2006 map by the United States Geological Survey showing varying seismic hazards across the U.S. with locations of nuclear reactors. Reactors in black are active; reactors in blue are proposed sites for the new model known as the AP1000. Probability of strong shaking increases from very low (white), to moderate (blue, green, and yellow), to high (orange, pink, and red). Credit: Kimberly Leonard/Center for Public Integrity.For more information on each nuclear reactor in our map, download the list. " target="_hplink"> map by the United States Geological Survey showing varying seismic hazards across the U.S. with locations of nuclear reactors. Reactors in black are active; reactors in blue are proposed sites for the new model known as the AP1000. Probability of strong shaking increases from very low (white), to moderate (blue, green, and yellow), to high (orange, pink, and red). Credit: Kimberly Leonard/Center for Public Integrity.

For more information on each nuclear reactor in our map, download the list.